"fait main | handmade”

Alisa Arsenault

Comfort, well-being, and familiarity, but also ability, resourcefulness, and know-how often come to mind when engaging with artisanal objects and the handmade. The exhibition fait main | handmade explores manual work in six artists’ practices; that is, it examines how the artists handle the material within their creative process and the way in which this handling manifests itself physically and conceptually in their works. The artists’ traditional and/or analog techniques, sometimes used directly and sometimes transformed through digital explorations, are mobilized in various ways. As manual work is often repetitive, this exhibition seeks to discover how recurrences affect the artists’ relationship with their work, their approach, and their day-to-day life. The artists use patterns and ways of working that are familiar to us, making the works more accessible. However, these artworks are also surprising and destabilizing in their distortions and reinterpretations of form, theme, and craft practice. They seem to exist in an intermediate state, between materialization and incompletion.In a text titled Intuitive Curation, Robyn Wilcox proposes that concepts such as embodied knowledge and intuition are encompassed within artisanal practices: “Craft is entwined with time and space. We weave it into the narrative of our daily lives and spaces through both use and presence.” fait main | handmade is a conversation about work and touch, about manipulation and materiality, and the ways in which these entwine with the artists’ processes at various times and in unexpected and layered ways. The processes themselves manifest through the works, thus preserving traces of the creative act.

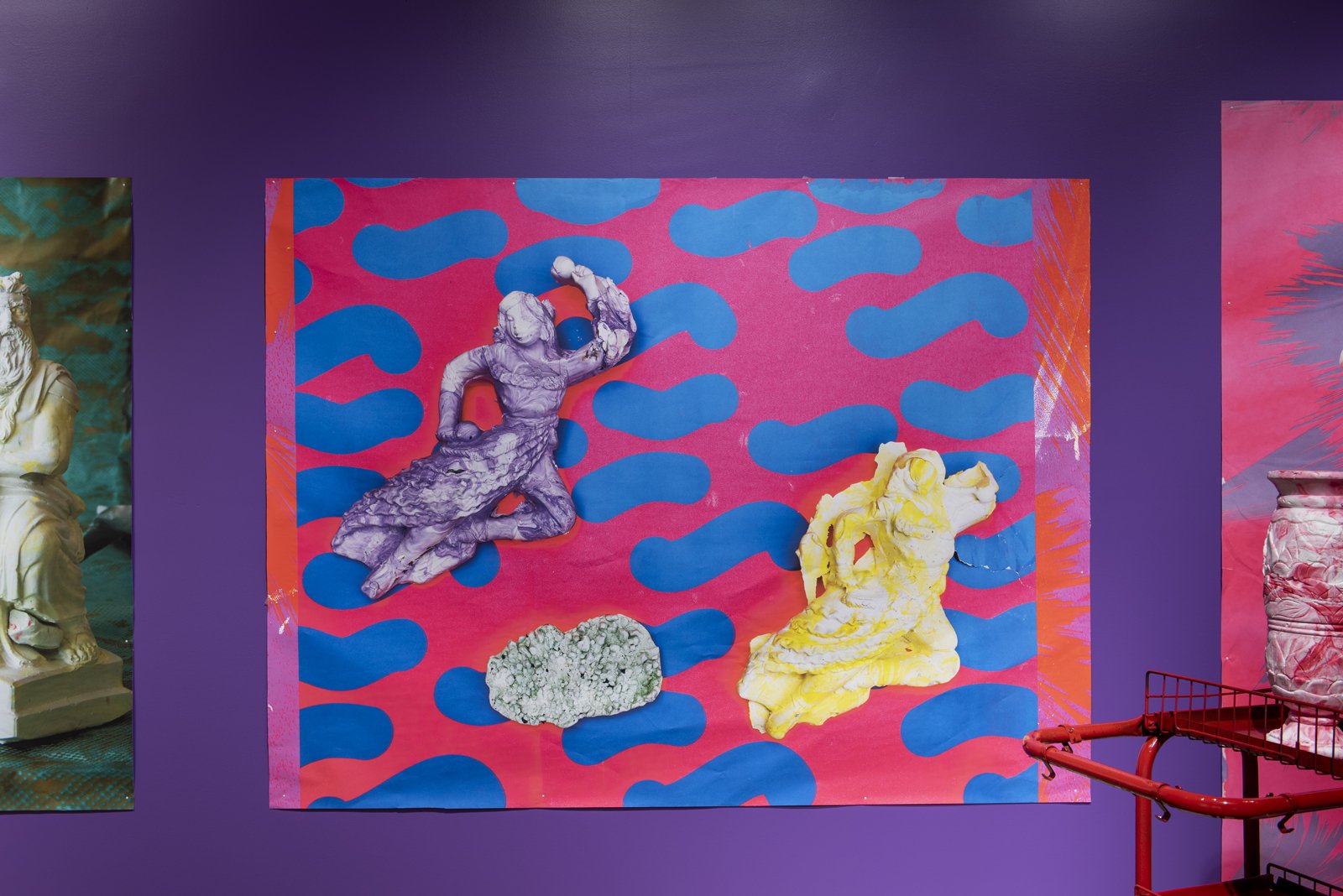

Jacinthe Loranger’s installation consists of giant ink-jet prints of still lifes composed of discarded or found objects that are cast by the artist. These items are represented on a larger-than-life scale, thus creating a landscape that belongs to the world of the object. Only one of these cast trinkets, a vase, is exhibited in the gallery space, revealing its actual size to the visitor. The floor of the gallery is also covered with printed papers. These prints mimic the texture of fabrics through saturation of ink and papier-mâché glue, which creates a certain ambiguity around the nature of the material that is shown. A projection of a campfire made from printed papers, cast logs and found objects accompanies these prints. The video shows smoke that undulates slowly as well as a soundtrack of a crackling fire, giving life to the crafted production. The composition is abundant and opulent and offers a field of possibility where playful and colorful objects meet, prompting a reflection on production and overconsumption, with as much derision and humor as there is depth.

The use of digital photographs of handmade objects is also reflected in the work Un lit comme une rivière, by Marjolaine Bourgeois. This work is inspired mainly by the Petitcodiac River and its ecosystem, and, more precisely, by the biodiversity that the river shelters. This watercourse, significant in the history of the Mi’gmaw and Acadian peoples, is located on the traditional unceded territory of the Wolastoqiyik and the Mi’gmaq. A quilt made up of digital prints of the artist’s needlework covers a bed-like structure, and, like a river, it pours out on both sides, flowing along the length of the gallery floor. Framed embroideries exhibited on the walls surrounding the “bed” show images of creatures, some of which inhabit the Petitcodiac’s ecosystem and prosper there. These embroideries are shown in their initial state, with their backs displayed, showing how they were made. This desire to reveal how an object was created, combined with details that denote an unfinished or broken appearance, such as the pieces of lace unraveling along the quilt, emphasizes the tactility of the materials with which Un lit comme une rivière is crafted. We see the same unbridled approach in the drawings of

Allie Gattor, Mating rituals of New Brunswick throughout the ages, with their disjointed and desultory lines. Unfamiliar with the region prior to creating this series, the artist imagines different scenarios and creates her own folklore of the province. The set of large-format drawings is made with unstable and scattered strokes. The artist’s work and unremitting effort are thus perceptible in the renderings. The margins of the paper around the drawing space, where Allie carries out her line and color tests, are also shown. Affixed to the wall with simple green adhesive tape, the set of drawings is frozen in an in-between state and engaged in endless production.

Andrea-Jane Cornell’s soundscape comprises multiple loops of various sounds, most of them produced with circular-shaped objects. The soundtrack is also played on a loop, resonating discreetly throughout the exhibition and conversing gently with the other works. Visitors hear murmurs from the moment they enter the space, although they can better grasp the subtleties and nuances of this recording in the small gallery, a more intimate and darker space. In this cubic space, the artist unveils the objects used during the creation of this sound piece, revealing a significant part of her process. As she explains: “The circular sound-processing techniques, which imply loops and cycles of amplification and re-recording, create a degradation of the signal in time that is felt through cyclical swells. In a way, the process dematerializes the solid objects, scattering their pieces across the gallery’s sound plane.” Displayed on a large table, these objects seem to exist in a state of momentary interruption. This way, the artist invites us to imagine various creation maneuvers and to create links between what is seen and what is heard in the space. The immobile objects aspire to be touched and manipulated, while the artist’s arrangement reveals their auditory potential.

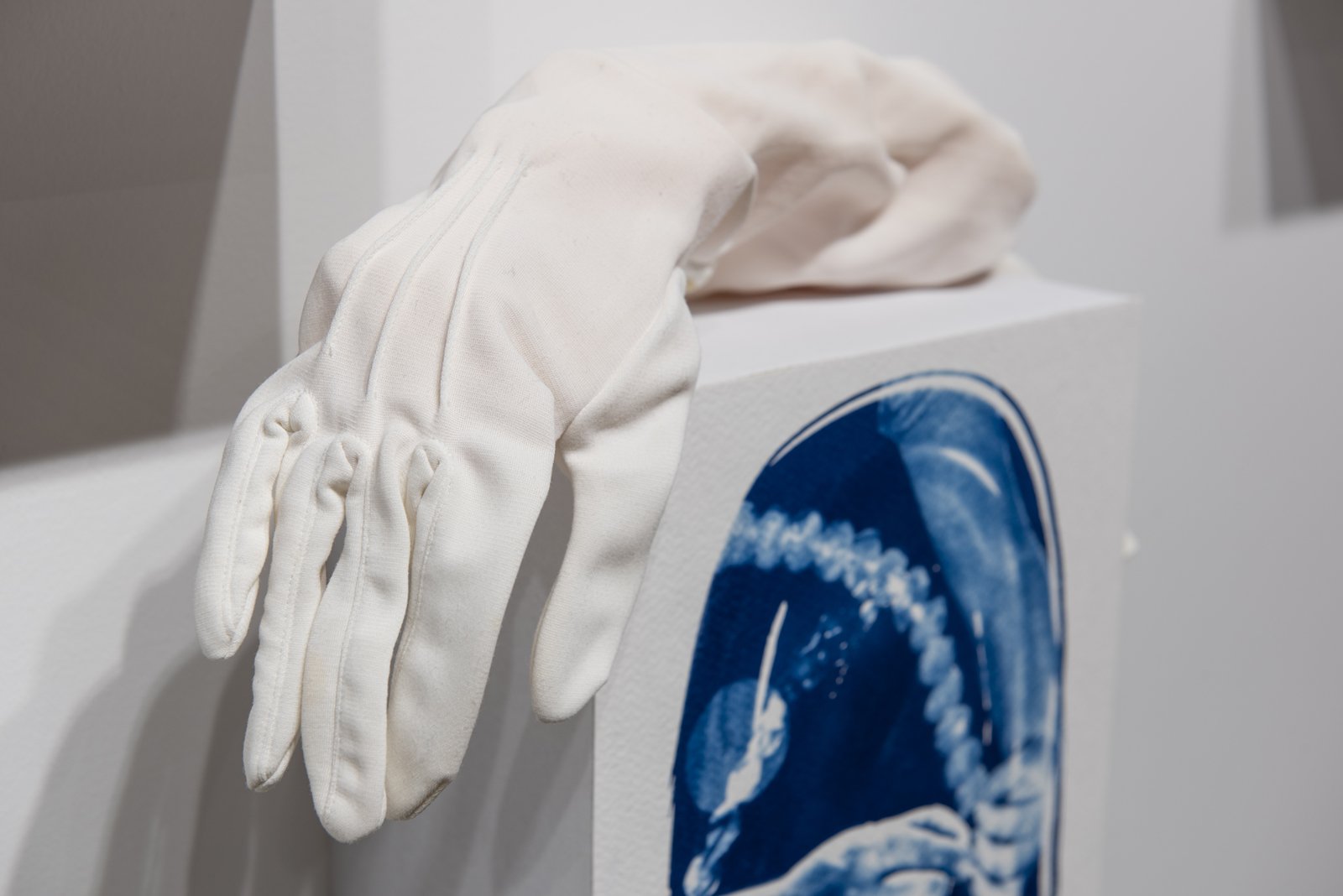

Amy Ash’s Learnscapes is both the archive of a workshop led by the artist in the exhibition space with participants from a community youth mentorship group and an interactive installation inspired by haptic learning and touch. The collaboration with a non-profit organization stems from the artist’s desire to work with the communities that are most affected by isolation, given the reality of the last two years as physical contact and touch have been strongly regulated. The arrangement of cyanotypes, textiles, and objects forms a trace that validates the unique and collaborative experience of interaction and exchange between the artist and the workshop participants. The production of the work is therefore a collective accomplishment and depends in large part on what took place during the workshop. The visitors can observe the installation, manipulate some of its elements and capture snippets of the experience that influenced the creation of these works. This experience is further embodied by photographs depicting the artist wearing the creations of the workshop participants. Accompanying the photographs are small sketches of the objects drawn directly onto the wall with tracing paper, as well as the poetic prompts that were handed out at the beginning of the workshop for inspiration. Both the approach and the presentation suggest the intimacy of this shared experience.

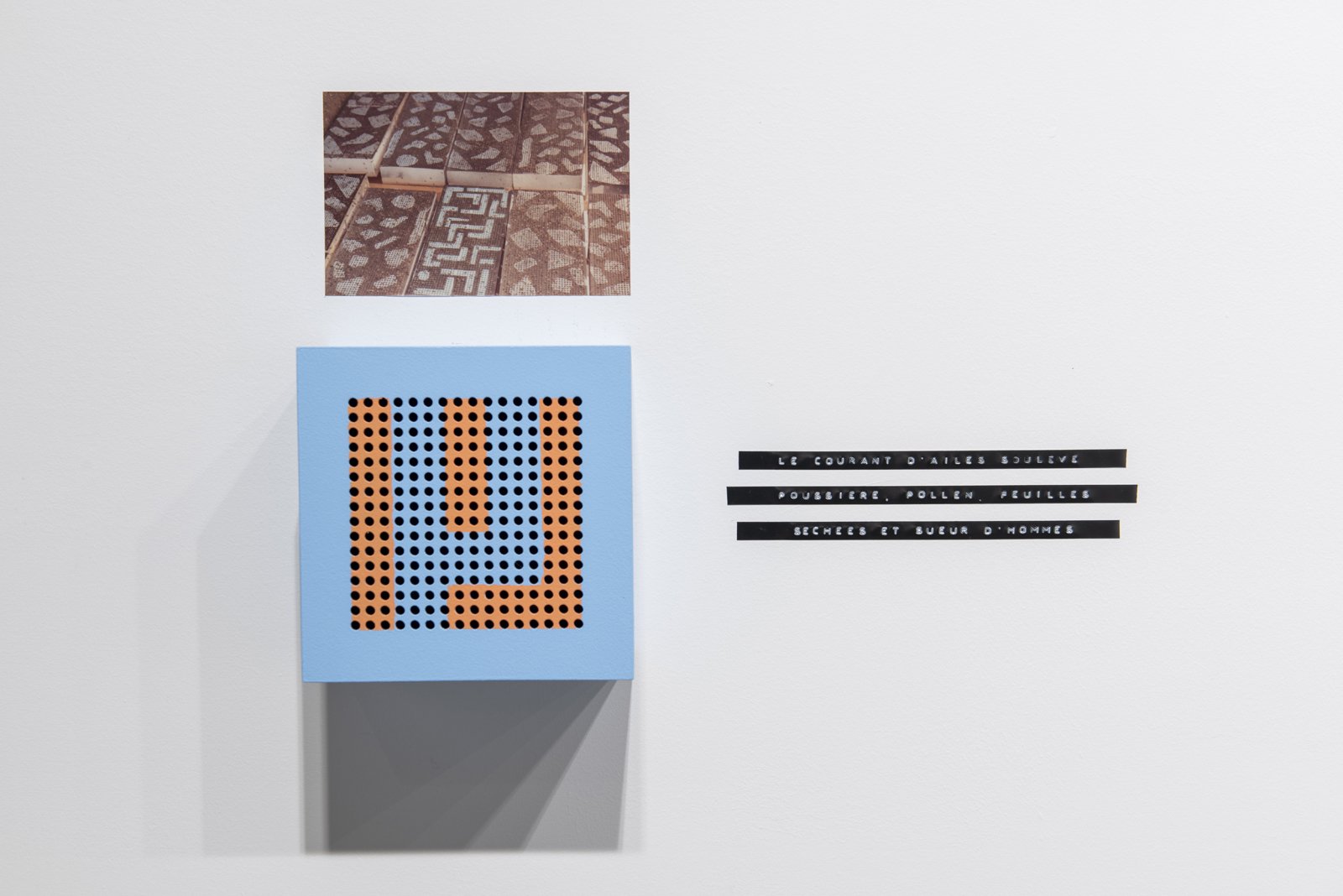

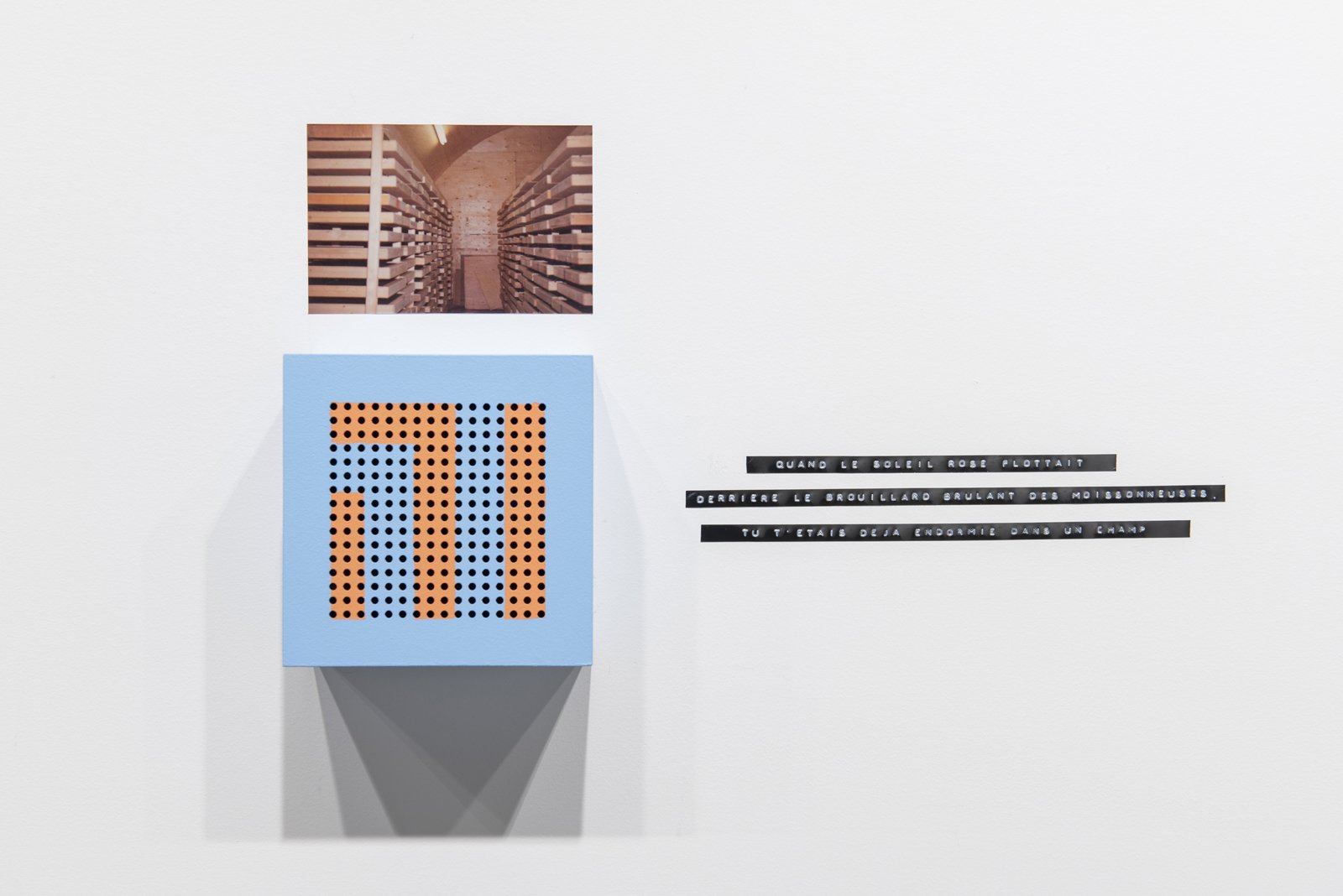

Les poinçonneuses by Zoé Fortier also contains a double, or even a triple, exploration. First, following an ethno-entomological approach, the artist takes interest in the connection between her family and leafcutting bees (Megachile). Through a series of interviews with her father, a contract beekeeper, Zoé questions her family business from an ecological standpoint, interpreting in a nuanced manner the evolution “of a nature that is less and less natural, and of the human labor that frames it”. Then, with the help of drawings that represent the artist’s family and of poems that she wrote following discussions with her father, Zoé undertakes a more intimate exploration of the father-daughter relationship, memory, and the passage of time. This work does not contain obvious visual markers linking it to craft, but rather it operates in the conceptual study of both labor and production, those of the beekeeper and of the Megachile bee, as well as those of the artist. It is through an interest in the process and an emphasis on the work required from all parties that this piece enters into dialogue with the overall exhibition.

"Specific experience of an abnormal meaningfulness”

Alisa Arsenault

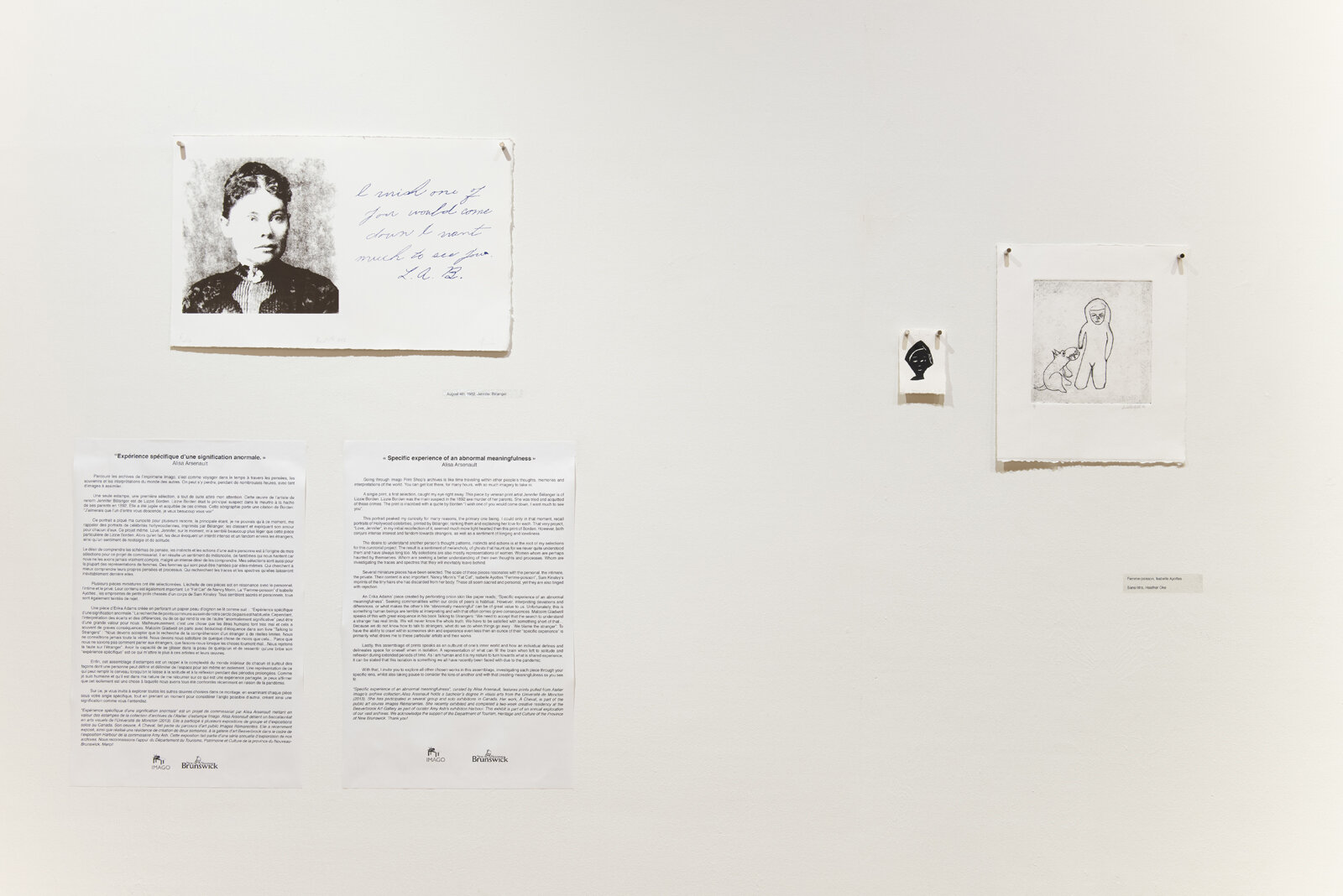

Going through Imago Print Shop’s archives is like time traveling within other people’s thoughts, memories, and interpretations of the world. You can get lost there, for many hours, with so much imagery to take in.

A single print, a first selection, caught my eye right away. This piece by veteran print artist Jennifer Bélanger is of Lizzie Borden. Lizzie Borden was the main suspect in the 1892 ax murder of her parents. She was tried and acquitted of these crimes. The print is inscribed with a quote by Borden “I wish one of you would come down, I want much to see you”.

This portrait piqued my curiosity for many reasons, the primary one being, I could only at that moment, recall portraits of Hollywood celebrities, printed by Bélanger, ranking them and explaining her love for each. That very project, “Love, Jennifer”, in my initial recollection of it, seemed much more light-hearted than this print of Borden. However, both conjure intense interest and fandom towards strangers, as well as a sentiment of longing and loneliness.

The desire to understand another person’s thought patterns, instincts and actions is at the root of my selections for this curatorial project. The result is a sentiment of melancholy, of ghosts that haunt us for we never quite understood them and have always long too. My selections are also mostly representations of women. Women who are perhaps haunted by themselves. Who are seeking a better understanding of their own thoughts and processes. Who are investigating the traces and specters that they will inevitably leave behind.

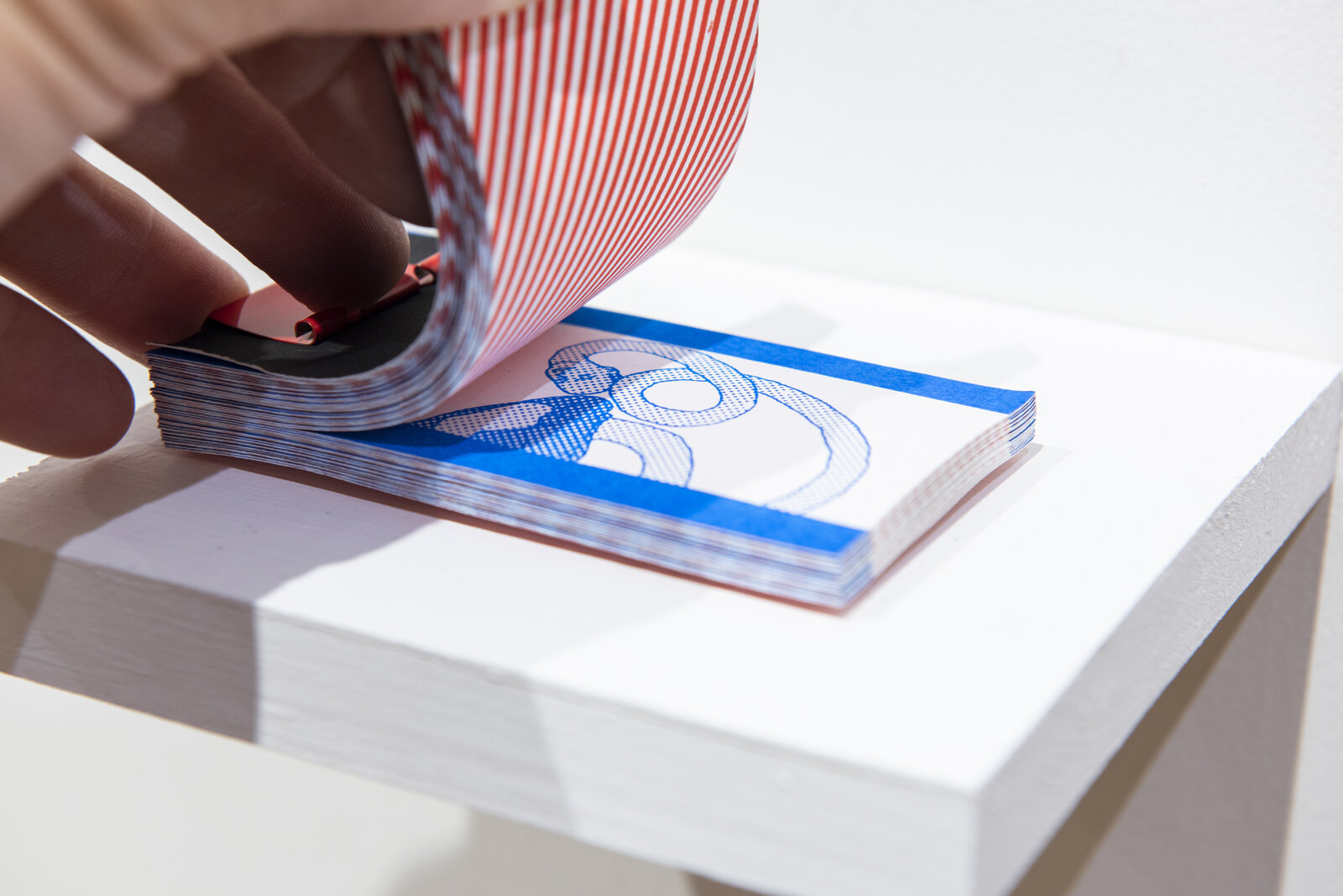

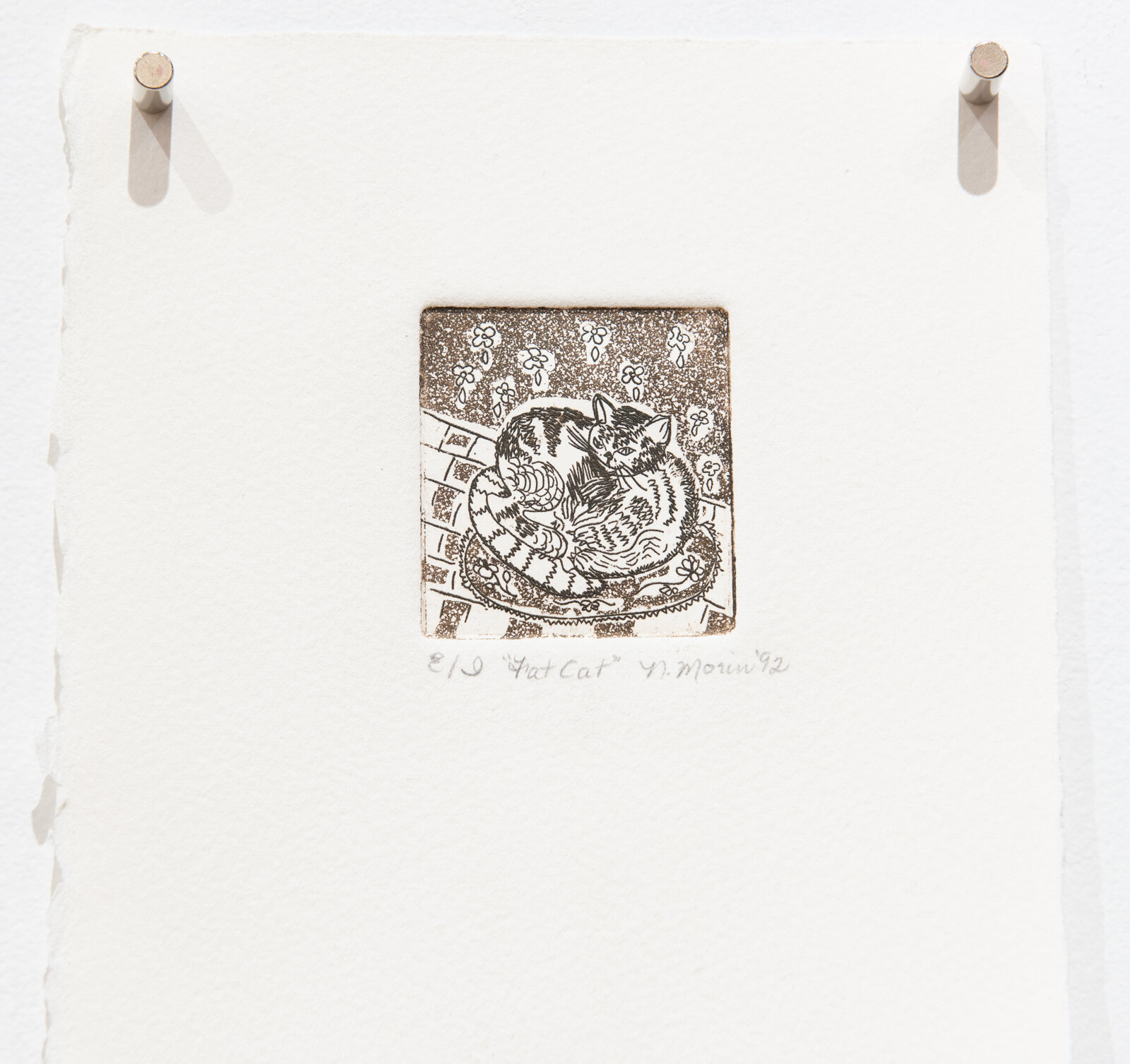

Several miniature pieces have been selected. The scale of these pieces resonates with the personal, the intimate, the private. Their content is also important. Nancy Morin’s “Fat Cat”, Isabelle Ayotte “Femme-poisson”, Sam Kinsley’s imprints of the tiny hairs she has discarded from her body. These all seem sacred and personal, yet they are also tinged with rejection.

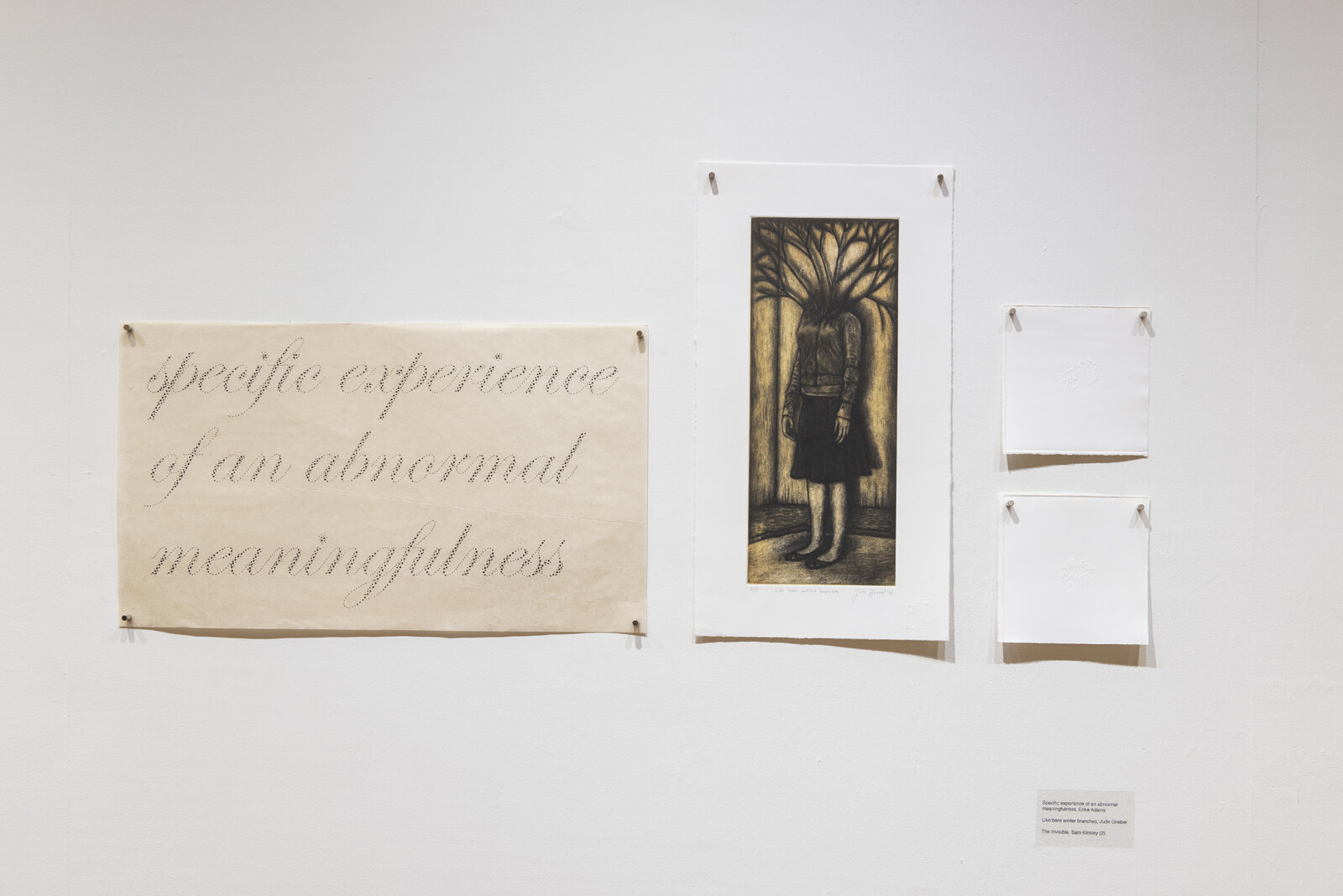

An Erika Adams’ piece created by perforating onion skin like paper reads; “Specific experience of an abnormal meaningfulness”. Seeking commonalities within our circle of peers is habitual. However, interpreting deviations and differences, or what makes the other’s life “abnormally meaningful” can be of great value to us. Unfortunately, this is something human beings are terrible at interpreting and with that often comes grave consequences. Malcolm Gladwell speaks of this with great eloquence in his book Talking to Strangers: “We need to accept that the search to understand a stranger has real limits. We will never know the whole truth. We have to be satisfied with something short of that…Because we do not know how to talk to strangers, what do we do when things go awry…We blame the stranger”. To have the ability to crawl within someone’s skin and experience even less then an ounce of their “specific experience” is primarily what draws me to these particular artists and their works.

Lastly, this assemblage of prints speaks as an outburst of one’s inner world and how an individual defines and delineates space for oneself when in isolation. A representation of what can fill the brain when left to solitude and reflection during extended periods of time. As I am human and it is my nature to turn towards what is shared experience, it can be stated that this isolation is something we all have recently been faced with due to the pandemic.

With that, I invite you to explore all other chosen works in this assemblage, investigating each piece through your specific lens, whilst also taking a pause to consider the lens of another and with that creating meaningfulness as you see fit.